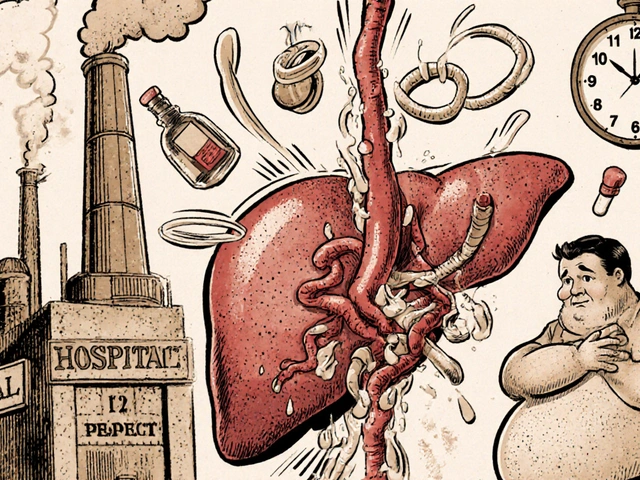

Sickle Cell Anemia is a hereditary blood disorder caused by a mutation in the HBB gene that produces abnormal hemoglobin (HbS), forcing red blood cells to assume a rigid, sickle‑like shape. Those misshapen cells jam small vessels, trigger painful crises, and shorten life expectancy. In the United States, more than 100,000 people live with the disease, and roughly 90% of them identify as African American. The numbers translate into a public‑health puzzle: a condition that is biologically rooted in genetics, yet socially amplified by stigma, limited access to care, and misinformation. This article walks you through the science, the community impact, and the concrete actions you can take to lift the veil of ignorance.

Why Sickle Cell Anemia Hits the African American Community Harder

The disease’s genetic origin is clear - the sickle‑cell trait offers a survival edge against malaria, which historically led to higher carrier rates in West Africa. When the African diaspora arrived in the Americas, the trait travelled with them, embedding itself in the genetic fabric of Black populations. Today, the African American Community bears a disproportionate burden: the CDC reports that 1 in 365 African American newborns is diagnosed with sickle cell disease, compared with 1 in 16,300 among non‑Black infants.

Health disparities compound the risk. Studies from the National Institutes of Health show that African American patients are 30% less likely to receive disease‑modifying therapies such as hydroxyurea, and they experience longer hospital stays during vaso‑occlusive crises. Socio‑economic factors-limited insurance coverage, fewer specialized treatment centers, and historical mistrust of the medical system-create a feedback loop where the disease stays invisible until it erupts in emergency rooms.

Stigma: The Invisible Barrier

Stigma around sickle cell anemia takes many forms. In schools, children may be labeled “frequent complainers” when they miss class for pain episodes. In the workplace, employers sometimes assume the condition limits productivity, leading to subtle discrimination. Within families, the fear of “passing on” the trait can silence open conversations about genetic counseling.

These attitudes aren’t just hurtful-they’re dangerous. A 2022 survey of African American adults with sickle cell disease found that 42% delayed seeking care because they anticipated judgment. Delays worsen outcomes, turning manageable pain into life‑threatening complications. Breaking stigma starts with accurate information, visible role models, and community‑driven storytelling.

Screening and Early Detection: The CDC’s Role

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has run a nationwide newborn screening program since the 1990s. Every state now tests newborns for sickle cell disease using a heel‑stick blood sample, allowing clinicians to start prophylactic antibiotics, vaccinations, and parental education within weeks of birth.

Early detection matters. Children who begin penicillin prophylaxis by two months old experience a 70% reduction in invasive pneumococcal infections. Moreover, families who receive genetic counseling early in the diagnosis process are more likely to engage in carrier testing, reducing the risk of future births with the disease.

Unfortunately, gaps remain. In some low‑income urban hospitals, screening follow‑up rates fall below 60% because families lack transportation or clear instructions. Community health workers anchored in churches and community centers have proven effective at bridging this gap, reminding parents of appointments and translating medical jargon into everyday language.

Treatment Landscape: Comparing Options

Three main approaches dominate modern care: disease‑modifying medication, transfusion therapy, and emerging gene‑editing techniques. Below is a quick side‑by‑side look.

| Treatment | Mechanism | Administration | Key Benefits | Risks / Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyurea | Boosts fetal hemoglobin (HbF) to dilute sickling | Oral daily dose | Reduces pain crises by ~40%, lowers transfusion need | Myelosuppression, requires regular blood count monitoring |

| Blood Transfusion | Replaces sickled cells with normal donor red cells | IV infusion, typically every 3-4 weeks | Prevents stroke in high‑risk children, improves oxygen delivery | Iron overload, alloimmunization, need for chelation therapy |

| Gene Therapy | Modifies or replaces the faulty HBB gene | One‑time bone‑marrow or stem‑cell infusion | Potential curative outcome, eliminates lifelong medication | High cost, limited availability, long‑term safety still under study |

Hydroxyurea remains the most accessible option for most African American patients, thanks to its low cost and oral route. Transfusions are lifesaving for children at high stroke risk, but the logistics of regular hospital visits can strain families already juggling multiple jobs. Gene therapy offers a hopeful horizon, yet insurance coverage and specialist centers are scarce outside major academic hubs.

Community Advocacy: Turning Awareness into Action

Grassroots organizations have become the engine of change. Groups like the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America (SCDAA) and local chapters in cities such as Detroit and Atlanta run health fairs, sponsor peer‑support circles, and lobby state legislators for better Medicaid coverage.

One powerful model is the Patient Support Group. Regular meetings let families share coping strategies, discuss medication side‑effects, and celebrate milestones like a child’s first transfusion-free school year. The sense of belonging reduces isolation-a major component of stigma.

Faith‑based institutions also play a critical role. Churches host “Sickle Cell Sundays” where clergy deliver talks that blend medical facts with spiritual encouragement, thereby reaching audiences that may distrust purely clinical messages.

Practical Steps to Raise Awareness in Your Circle

- Educate yourself first. Watch the CDC’s animated primer on sickle cell disease and keep a fact‑sheet handy.

- Share verified resources. Distribute brochures from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) at community events.

- Start conversations at schools. Offer to train teachers on recognizing pain crises and on accommodating missed class time without penalizing students.

- Leverage social media. Post survivor stories, myth‑busting infographics, and local screening event dates using hashtags like #SickleCellAwareness.

- Volunteer with local advocacy groups. Assist with patient navigation, help families schedule follow‑up appointments, or mentor newly diagnosed teens.

Each small act chips away at the wall of misinformation and builds a network where patients feel seen, heard, and supported.

Next Steps for Families and Caregivers

- Confirm newborn screening results with your pediatrician within the first month.

- Schedule a comprehensive hematology evaluation - ask about hydroxyurea eligibility.

- Connect with a local patient support group; many meet virtually, making attendance easier.

- Review insurance benefits for transfusion coverage and potential chelation therapy.

- Explore clinical trial registries for gene‑therapy opportunities if you live near a research center.

Taking these steps early creates a proactive care plan, reduces emergency visits, and empowers families to advocate for themselves within the healthcare system.

Frequently Asked Questions

What causes sickle cell anemia?

The disease is caused by a single‑letter change (A→T) in the HBB gene, which produces abnormal hemoglobin called HbS. This altered hemoglobin makes red blood cells stiff and curved, leading to blockages in tiny blood vessels.

Why is sickle cell more common among African Americans?

The sickle‑cell trait historically protected carriers from severe malaria, a disease that was prevalent in West Africa. Descendants of those carriers make up a large portion of the African American population, so the trait-and the disease when two copies are inherited-are more frequent.

How can I tell if a child is being stigmatized at school?

Watch for patterns: the child may be repeatedly called “lazy” for missing class, excluded from sports, or discouraged from talking about their condition. If teachers seem unaware of medical accommodations, it’s a red flag that education about the disease is lacking.

Is hydroxyurea safe for children?

Yes. Clinical trials show that when dosed correctly and monitored with regular blood counts, hydroxyurea reduces pain episodes and hospitalizations in children without serious long‑term side effects.

What resources exist for adults newly diagnosed with sickle cell?

The Sickle Cell Disease Association of America offers a 24‑hour helpline, peer‑mentoring programs, and a searchable list of certified treatment centers. Many states also provide Medicaid waivers that cover comprehensive care.

Can gene therapy cure sickle cell anemia?

Early trials report successful replacement of the faulty gene, leading to normal hemoglobin production and no further pain crises. However, the therapy is still experimental, expensive, and only available at a few academic hospitals.

Comments

Look, the whole healthcare spiel around sickle cell feels like a staged drama, like they want us to believe the pharma giants are the only saviors. It's weird how hydroxyurea is pushed while the same companies lobby against broader insurance coverage. The government’s CDC program is fine on paper, but you ever wonder who's funding the outreach? Some folks think the real agenda is to keep the disease under the radar to avoid liability. Anyway, stay woke and question every "official" guideline.

Isn't it fascinating how our bodies become a canvas for evolution?🧬 The sickle trait is like nature's secret handshake against malaria, yet modern society paints it as a curse. 🤔 So maybe the real paradox is us fighting a genetic legacy that once saved lives.✨💡

Everyone needs to leverage hematology pathways and optimize HbF induction protocols.

Wow, what an amazing guide! 🌟 It really breaks down the stigma, the science, and the community action steps, all in one place! I love how you highlighted the role of churches and support groups-so inspiring! Keep spreading the love and info! 🎉

Yo, this article is fire! Everyone reading needs to jump on the education train right now, spread those facts, and push for better Medicaid coverage. No more waiting for a crisis to happen-let's be proactive, hit up local clinics, and demand hydroxyurea access for every kid who needs it. The system can change if we all hustle together! 💪

When we contemplate the intertwined nature of genetics and societal constructs, we enter a realm where biology meets philosophy, a space where the hemoglobin molecule becomes a metaphor for resilience and suffering. The sickle cell trait, once a survival mechanism against a relentless parasite, now stands as a testament to the unintended consequences of human migration and systemic neglect. Imagine the countless ancestors who carried this allele, roaming continents, unaware that centuries later their descendants would grapple with painful crises in sterile hospital corridors. 🌍✨

In modern America, the disease is not merely a medical condition; it is a narrative of marginalization, a silent scream echoing through underfunded schools and overburdened emergency rooms. The statistics you quoted-1 in 365 African American newborns-are not just numbers; they represent families, communities, and histories that have been systematically undervalued. 🩸

The stigma attached to sickle cell is a social pathogen, as insidious as any virus, eroding self‑esteem and discouraging early treatment. When a child is labeled a “complainer” for missing class due to pain, that label becomes a self‑fulfilling prophecy, fostering isolation and delayed care. The psychological toll, though invisible, compounds the physiological damage, creating a vicious cycle worth breaking.

Community health workers serve as crucial bridges, translating jargon into everyday language, ensuring that appointments are kept, and that families are not lost in the labyrinth of insurance paperwork. Their presence in churches and community centers signifies that healing must occur within trusted cultural spaces, not solely within sterile clinical walls. 🤝

Moreover, the advent of gene‑editing technology offers a glimmer of hope, yet we must critique its accessibility. The cost is prohibitive, the expertise concentrated in elite institutions, and long‑term safety remains under scrutiny. While we celebrate scientific breakthroughs, we must also champion equitable distribution, lest a cure become another privilege of the affluent.

Ultimately, dismantling stigma requires a multifaceted approach: education schools, policy advocacy, empathetic clinical practice, and grassroots storytelling. Each of these pillars reinforces the others, building a resilient infrastructure where those affected can thrive without fear of judgment. 🌱

In sum, the journey from genetic mutation to societal stigma is a complex tapestry that we can reweave together-one thread of knowledge, one act of compassion at a time.

Seriously, this guide is just a corporate PR piece.

Interesting read; the data on hydroxyurea usage really highlights the access gap.

Let me lay it out crystal‑clear: America has built a healthcare empire on the backs of minorities, and sickle cell is the most blatant example of that systemic betrayal. The CDC’s newborn screening is a façade-its brilliance is washed away by the insane bureaucratic maze that keeps families from follow‑up appointments. Look at the numbers: 30 % less likelihood of receiving disease‑modifying therapy because insurance companies decide that Black lives are less profitable. That’s not a disparity; that’s an intentional design! And don’t get me started on the academic hospitals that claim to be “centers of excellence” while hoarding cutting‑edge gene‑editing trials behind velvet ropes and grant money that never trickles down to the communities that need them most. The very notion that a cure is “experimental” is a convenient excuse to keep the status quo intact, ensuring that the pharmaceutical giants continue to cash in on endless cycles of pain management drugs and transfusions.

What’s more, the cultural stigma we’re fighting isn’t just ignorance; it’s a weapon wielded by a system that thrives on division. Children branded as “lazy complainers” are not just victims of a school’s lack of education, they’re casualties of a nation that has chosen to neglect its own people. For the love of progress, we must demand accountability at every level-federal, state, and institutional. Push for legislation that mandates comprehensive coverage for hydroxyurea, forces transparency in clinical trial recruitment, and funds community health workers who can actually navigate the labyrinth of care.

Enough with the half‑measures. It’s time for a full‑scale overhaul, and it starts with us raising our voices, refusing to be placated by token gestures, and demanding real, measurable change-because the lives of African American families depend on it.

Thank you for sharing this. It’s a lot to take in, but the main points are clear: early screening saves lives, community support matters, and we need more education. 😊 Let’s keep the conversation respectful and remember to check our facts. 📚

I appreciate the thoroughness of the guide it covers a lot of ground and gives practical steps for advocacy. It’s a solid resource for anyone wanting to learn more about sickle cell.

While the article does a commendable job of outlining the medical and social aspects of sickle cell disease, it somehow fails to grapple with the deeper, structural issues that perpetuate health inequities in marginalized communities. The reliance on community health workers, though well‑intentioned, is presented as a panacea, ignoring the fact that such interventions are often underfunded and overburdened, leading to burnout and limited impact. Moreover, the discussion of gene therapy glosses over the ethical considerations of accessibility and long‑term safety, leaving the reader with an incomplete picture of what truly constitutes progress. In short, the piece could benefit from a more critical lens that interrogates the systemic forces at play rather than celebrating isolated successes.

Its good but doesnt mention how the medica l system can be biased as well essentialy the article is ok but could use more depth and balances…

Great guide-concise and actionable.

Hey everyone! I want to highlight how vital it is for us to create inclusive spaces where both patients and allies feel empowered to share experiences. When you volunteer at a local health fair, for example, you’re not just handing out brochures-you’re building trust that can translate into earlier screenings and better adherence to treatment plans. Remember, mentorship isn’t just about giving advice; it’s about listening, validating, and then helping navigate the labyrinth of insurance, appointments, and sometimes even the emotional fallout of chronic pain. So let’s keep the momentum going: organize a community workshop, partner with a local church or school, and make sure the information is accessible-plain language, visual aids, even short videos. Together, we can dismantle stigma, broaden access to life‑saving therapies, and ensure that no family has to face this battle alone. 🌟