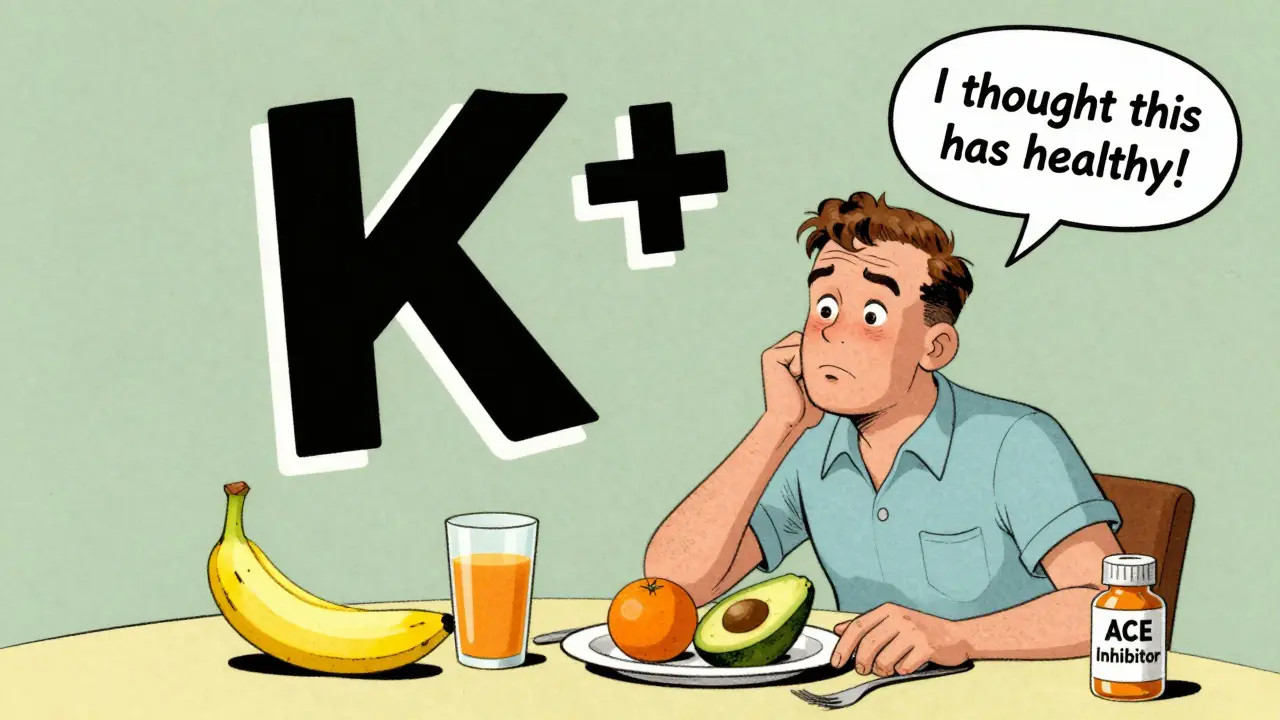

When you're taking an ACE inhibitor for high blood pressure, heart failure, or kidney disease, one of the biggest hidden risks isn't another drug-it's what's on your plate. ACE inhibitors are lifesavers for millions, but they can quietly push potassium levels too high, leading to a dangerous condition called hyperkalemia. And unlike side effects like cough or dizziness, this one often flies under the radar until it's too late. The good news? You can prevent it. Not with more pills, but with smarter eating.

How ACE Inhibitors Raise Potassium Levels

ACE inhibitors work by blocking a system in your body called RAAS-the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. This system normally tells your kidneys to hold onto salt and push out potassium. When you take an ACE inhibitor, that signal gets cut off. Aldosterone, the hormone responsible for kicking potassium out of your body, drops by 40% to 60%. That means your kidneys start holding onto potassium instead of flushing it out.

Here’s the catch: your kidneys handle over 90% of your body’s potassium. If they’re already struggling-because you have diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or just older age-they can’t compensate. A 2021 study in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology found that 10.6% to 23.9% of people on ACE inhibitors develop high potassium. For those with an eGFR below 60, the risk jumps to more than triple.

Who’s Most at Risk?

You’re not equally at risk just because you’re on an ACE inhibitor. Some people need to be extra careful:

- People over 75

- Those with diabetes, especially if they have protein in their urine

- Patients with heart failure (NYHA Class III or IV)

- Anyone with kidney function below 45 mL/min

- People taking other potassium-raising drugs like spironolactone, trimethoprim, or NSAIDs

A 2021 study showed diabetic patients on ACE inhibitors had a 47% higher chance of developing hyperkalemia than non-diabetics. And if you’re on both an ACE inhibitor and a potassium-sparing diuretic? Your risk spikes by nearly threefold.

Which Foods Are the Real Troublemakers?

Not all potassium is created equal. Some foods are packed with it-and if you’re on an ACE inhibitor, even a single serving can tip the scales. The National Kidney Foundation recommends limiting potassium to under 2,000 mg per day if your eGFR is below 45. Here’s what to watch out for:

- Bananas - 422 mg per medium fruit

- Oranges and orange juice - 237 mg per medium orange, over 400 mg per cup of juice

- Potatoes - 926 mg in a medium baked potato

- Spinach (cooked) - 839 mg per cup

- Avocados - 708 mg per cup, sliced

- Tomatoes and tomato products - 292 mg per medium tomato, over 900 mg per cup of sauce

- Sweet potatoes - 542 mg per medium potato

- Coconut water - 1,150 mg per 16 oz bottle

- Legumes - beans and lentils pack 600-800 mg per cup

- Salt substitutes - many contain potassium chloride, which can add hundreds of milligrams per teaspoon

Here’s the irony: many of these foods are labeled "healthy." But for someone on an ACE inhibitor, "healthy" can mean dangerous. A 2022 study found that 68% of patients couldn’t correctly identify three high-potassium foods from a common list. That’s why education matters more than ever.

What You Can Still Eat (and How to Make It Safer)

You don’t have to give up vegetables or fruits entirely. You just need to be smart.

Leaching is your friend. For potatoes, sweet potatoes, and root vegetables, cutting them into small pieces, soaking them in warm water for at least 2 hours, then rinsing and boiling them can reduce potassium by up to 50%. Do the same with leafy greens like spinach-blanch them first, then rinse well.

Choose lower-potassium alternatives:

- Instead of bananas: apples, berries, grapes, pineapple

- Instead of oranges: cranberry juice, apple juice

- Instead of white potatoes: rice, pasta, noodles

- Instead of spinach: lettuce, cabbage, cucumber

- Instead of avocado: hummus (in moderation) or olive oil

- Instead of coconut water: plain water, herbal tea, or diluted apple juice

Portion control matters. One medium banana might be too much, but half a banana with oatmeal? That’s manageable. A 2023 review in the American Journal of Medicine found that strict adherence to potassium limits cut hyperkalemia risk by 57%.

Monitoring and When to Call Your Doctor

Don’t wait for symptoms. Hyperkalemia often has none-until it causes a heart rhythm problem. That’s why regular blood tests are non-negotiable.

Your doctor should check your potassium and kidney function:

- Before you start the ACE inhibitor

- 7 to 14 days after starting

- After any dose change

- Every 4 months if you’re stable

If your potassium rises above 5.0 mmol/L, your doctor may pause the ACE inhibitor, adjust your dose, or add a potassium binder like patiromer or sodium zirconium cyclosilicate. These newer drugs help bind potassium in your gut so it doesn’t get absorbed. Studies show they reduce the need to stop ACE inhibitors by over 40%.

Dietary Counseling Makes a Difference

Reading a list isn’t enough. A 2021 study in the American Journal of Kidney Diseases found that patients who got personalized counseling from a renal dietitian cut their hyperkalemia rates by 34% compared to those who just got printed handouts.

Ask for a referral to a dietitian who specializes in kidney disease. They’ll help you build a meal plan that fits your taste, culture, and lifestyle. Tools like the "Renal Diet Helper" app can scan barcodes and track potassium intake. One Reddit user shared how she avoided a hospital trip after learning her "healthy" protein powder had 700 mg of potassium per scoop.

What About Potassium Supplements?

Never take potassium supplements unless your doctor specifically prescribes them. Even over-the-counter salt substitutes can be dangerous. Many contain potassium chloride, and a single teaspoon can deliver 800 mg of potassium. That’s nearly half your daily limit.

The Bottom Line

ACE inhibitors are among the most effective drugs we have for protecting your heart and kidneys. But they don’t work in isolation. Your diet plays a direct role in whether they help-or harm.

It’s not about perfection. It’s about awareness. Know your numbers. Know your foods. Know your limits. And don’t be afraid to ask your doctor or dietitian for help. With the right tools, you can keep taking your medication, stay healthy, and avoid the silent danger of high potassium.

Comments

bro i ate a whole avocado for breakfast and now my heart feels like it’s doing the cha-cha. thanks for the heads up, i guess i’m officially a walking potassium bomb 🍑💀

This is such a critical point-RAAS suppression leading to aldosterone drop is textbook, but most patients never get this explained in plain terms. The 40–60% reduction in aldosterone is the linchpin. Without that mechanism understood, dietary counseling is just noise.

I’ve been on lisinopril for 8 years and never knew spinach could be this dangerous. I’ve been blending a cup of raw spinach into my smoothie every morning thinking I’m being healthy. Holy crap. Gonna start blanching everything now.

lol i just googled "coconut water potassium" after reading this and found out my "natural hydration" drink has more potassium than a banana. my gym buddy and i have been sharing bottles like they’re Gatorade. oops.

they say "healthy foods" but they never say "these healthy foods might kill you if you’re on meds". why is that? because Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know you can’t just eat like a vegan hippie and take your pill. it’s all profit. stop trusting labels.

this is so important!! 🙌 i’ve been telling my mom for months to stop drinking coconut water and she kept saying "it’s natural!" now i’ve got a link to send her 😅

let’s be real-this whole thing is a bureaucratic trap. you’re told to eat clean, then told to avoid every vegetable that doesn’t come in a plastic bag. the system wants you docile, dependent, and on 37 different meds. potassium isn’t the enemy. the lack of real nutritional education is.

i had no idea leaching worked. my grandma taught me how to soak potatoes in water before frying them-said it made them "crispier." i thought she was just old-school. turns out she was a renal diet ninja. 🙏 i’m gonna try this with my sweet potatoes tomorrow.

I’ve been a renal dietitian for 12 years and this post nails it. The real win here is the emphasis on personalized counseling. Printed handouts? Useless. One 30-minute conversation with a dietitian who asks "what do you actually eat on Sundays?" changes lives. Don’t skip the referral.

y’all are overthinking this. just stop eating bananas, potatoes, and coconut water. done. you don’t need a PhD in nephrology to know that. i’ve been on benazepril for 5 years and i eat apples, rice, and chicken. simple. life’s too short for avocado toast on a pill like this.

i think the FDA knows about this. i think they let it slide because if people knew how many "healthy" foods were dangerous, they’d stop taking the meds. and then the pharmaceutical companies would lose billions. this is a quiet genocide. they don’t want you to know.

this is a psyop. potassium is not the enemy. the real enemy is the salt they add to processed food so you get thirsty and buy more bottled water… which is then laced with potassium chloride by the government to control the masses. i’ve seen the documents. they’re hiding it behind "kidney disease".

in india we have so many potassium rich foods like coconut, banana, lentils, and we still have low rates of hyperkalemia because our people are naturally more active and eat less processed food. the problem isn't the food, it's the sedentary american lifestyle combined with overprescribing. you need exercise, not just diet changes. i've seen this in my village-grandma on blood pressure meds eats mangoes daily and walks 5km. she's fine. you're just lazy.

It is both lamentable and indicative of the current state of public health literacy that individuals are unaware of the biochemical consequences of pharmacological intervention. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is not a trivial pathway; its suppression necessitates rigorous dietary vigilance. To equate dietary modification with mere "common sense" is to misunderstand the very foundation of clinical pharmacology. This is not a lifestyle choice-it is a physiological imperative.

thank you for writing this. my dad is on an ACE inhibitor and he loves his sweet potatoes. i’m going to show him the leaching trick. he’s stubborn but he’ll listen if i say it’s from a doctor’s advice. ❤️