Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) work like a switch-turning off the stomach’s acid production. For many people, they’re a lifeline. If you’ve had heartburn that won’t quit, or an ulcer that won’t heal, PPIs like omeprazole or esomeprazole can make life bearable. But what happens when you take them for months? Or years? The truth is, these drugs aren’t harmless. And too many people keep taking them long after they’re needed.

How PPIs Actually Work

PPIs don’t just reduce acid-they shut it down at the source. They target the proton pumps in your stomach lining, the final step in acid production. Unlike antacids that neutralize acid after it’s made, or H2 blockers like famotidine that only partly block production, PPIs stop acid at the root. That’s why they’re so effective. For severe GERD or healing erosive esophagitis, they work in over 90% of cases. But that power comes with trade-offs.

They need to be taken 30 to 60 minutes before a meal to work properly. That’s because they activate in acid, and food triggers acid release. If you take them after eating, they won’t do their job. Most prescription PPIs come in 10mg to 40mg doses. Over-the-counter versions are capped at 20mg-and the FDA says you shouldn’t use them for more than 14 days at a time, and no more than once every three months. Yet, studies show about 25% of people using OTC PPIs keep going past that limit, often without talking to a doctor.

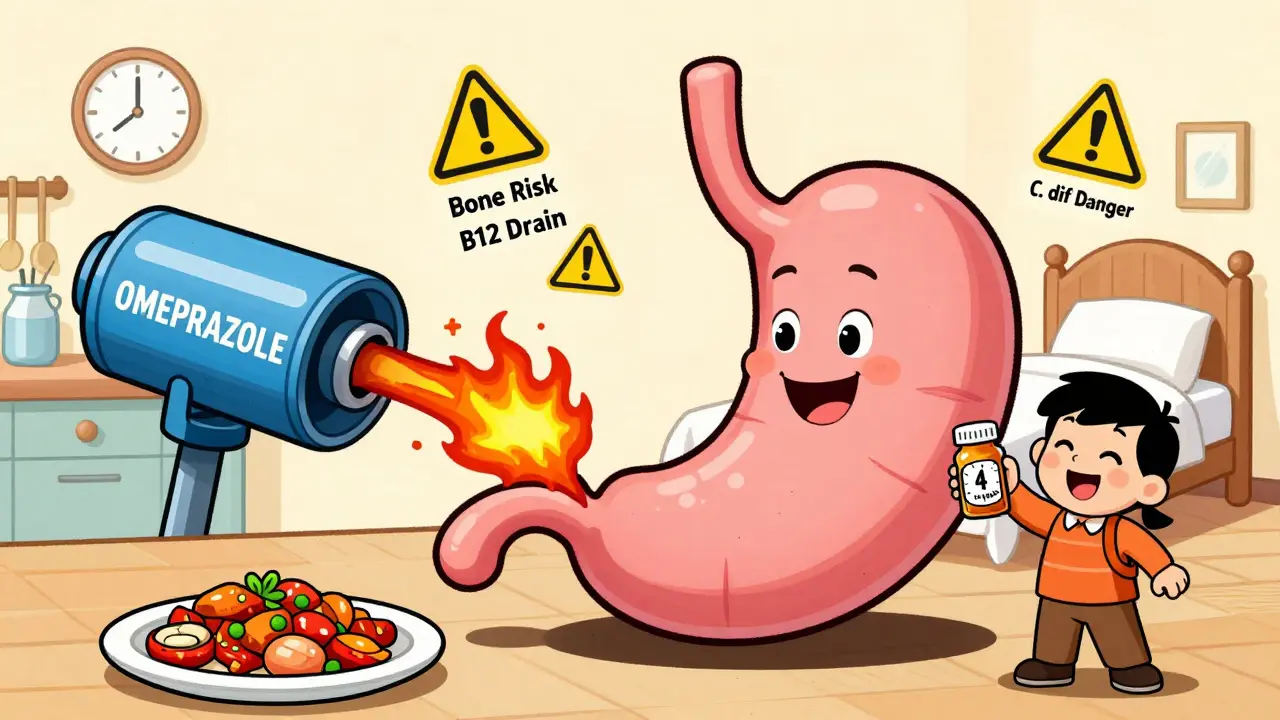

The Hidden Risks of Long-Term Use

Long-term PPI use isn’t just about feeling better. It’s about what your body loses when acid stays suppressed for too long. The FDA has issued seven safety warnings since 2010, and most of them are tied to chronic use.

One of the clearest risks is bone fractures-especially hip fractures. A 2017 study found that people who took PPIs for four years had a 42% higher risk. After six to eight years? The risk jumped to 55%. The good news? That risk drops back to normal within two years of stopping. Your bones aren’t permanently damaged-you just need to get off the drug.

Then there’s magnesium. It’s rare, but serious. About 0.5% to 1% of long-term users develop low magnesium levels. Symptoms? Muscle cramps, tremors, irregular heartbeat. The FDA now says doctors should check magnesium levels in anyone on PPIs for more than a year. If it drops too low, you might need supplements-or to stop the PPI altogether.

Vitamin B12 deficiency is another quiet problem. About 10% to 15% of people on PPIs for two years or more develop it. Why? Acid helps your body pull B12 out of food. Less acid = less absorption. Symptoms like fatigue, numbness, or memory issues can be mistaken for aging-until a blood test reveals the real cause.

Clostridioides difficile (C. diff) infections are more common in PPI users. The risk is 1.7 to 2 times higher, especially in hospitals or nursing homes. That’s because stomach acid normally kills harmful bacteria. When it’s gone, C. diff can take over. Severe cases can lead to life-threatening diarrhea.

There’s also a rare but real risk of acute interstitial nephritis-a kidney inflammation that can lead to chronic kidney disease. Studies show a 20% to 50% increased risk. It’s not common, but it’s serious enough that doctors now watch kidney function in long-term users.

What About Dementia, Heart Disease, or Cancer?

You’ve probably seen headlines linking PPIs to dementia, heart attacks, or stomach cancer. But here’s the catch: most of those studies didn’t prove PPIs caused the problem. They just saw that people taking PPIs were more likely to have those conditions. Why? Because the people who need long-term PPIs often have other health issues-obesity, diabetes, poor diet, smoking. Those are the real culprits.

Dr. William Ravich from Yale Medicine put it simply: “Many of the studies linking PPIs to dementia or heart disease weren’t about PPIs. They were about patients who happened to be on PPIs.”

One 2023 study claimed a 44% higher dementia risk, but later research couldn’t repeat those results. The same goes for stomach cancer. While long-term acid suppression can cause changes in stomach cells, there’s no solid evidence it leads to cancer in humans. One rare case of a neuroendocrine tumor was reported after 15 years of use-but that’s an outlier, not a trend.

The only confirmed long-term risks are the ones the FDA has flagged: fractures, low magnesium, B12 deficiency, C. diff, and kidney inflammation. Everything else? Still up for debate.

When Should You Stop?

You shouldn’t stop PPIs cold turkey. About 40% to 80% of people who quit suddenly get worse-way worse. That’s because your stomach overcompensates. It ramps up acid production to make up for the long silence. This is called rebound acid hypersecretion. It feels like your GERD came back with a vengeance.

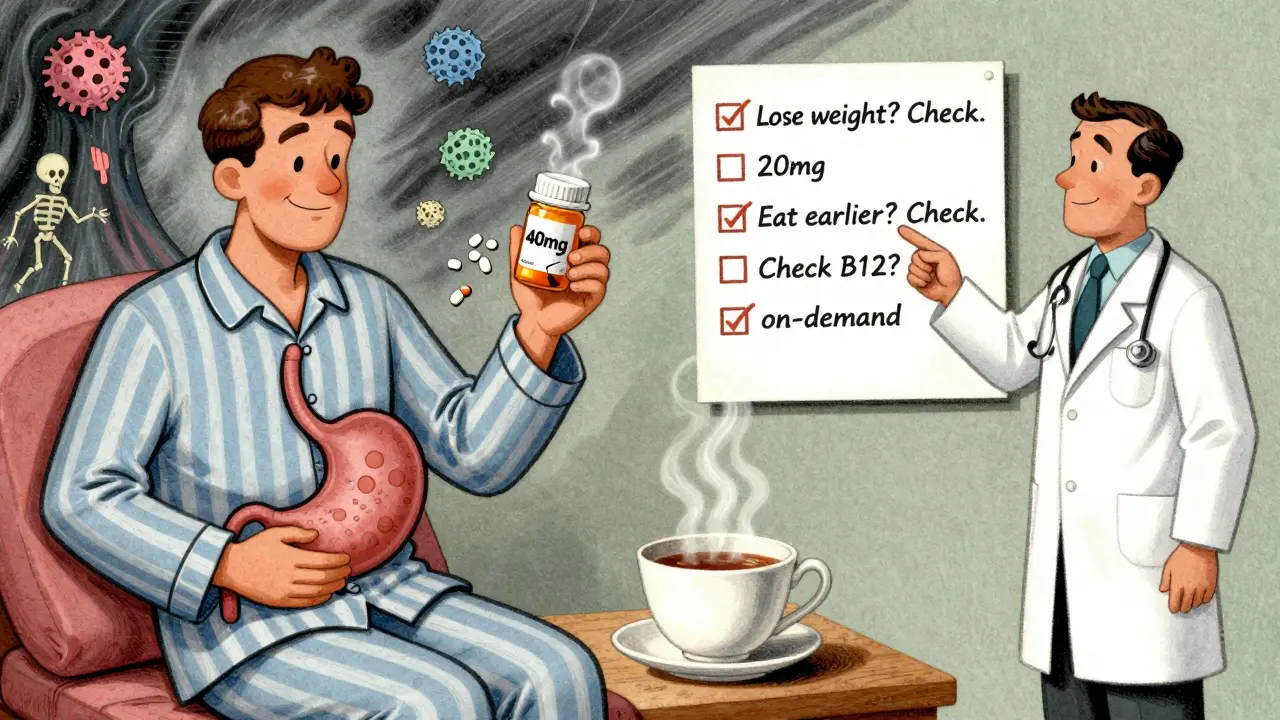

The American College of Gastroenterology recommends a slow, smart taper:

- Reduce your dose by half-for example, from 40mg to 20mg.

- Wait 1 to 2 weeks. If symptoms stay under control, reduce again.

- Once you’re at the lowest dose, switch to taking it only when you need it-on-demand.

- After a few weeks of on-demand use, try stopping completely.

Some people can stop in a few weeks. Others need months. It depends on how long they’ve been on it, why they started, and how their body reacts.

Doctors also recommend “drug holidays”-trying to stop every 6 to 12 months. Even if you need to go back on, it gives your body a reset. And if you’re on PPIs for dyspepsia without an endoscopy? You’re likely overusing them. Most cases of simple indigestion don’t need acid suppression.

What to Do Instead

If you’re on a PPI for mild GERD, ask yourself: Could lifestyle changes help? Losing weight, avoiding late-night meals, cutting out coffee or spicy food, and elevating the head of your bed can work better than pills for many people. H2 blockers like famotidine are less potent than PPIs, but they’re safer for occasional use. Antacids like Tums or Maalox work fast and have no long-term risks.

For people with true, diagnosed GERD or ulcers, PPIs are still the gold standard. But even then, the goal isn’t lifelong use-it’s symptom control with the lowest possible dose. If you’ve been on a PPI for more than 4 to 8 weeks for uncomplicated heartburn, you should talk to your doctor about weaning off.

The Bigger Picture: Why So Many People Are on PPIs

Over 15 million Americans take prescription PPIs daily. Another 7 million use OTC versions long-term. That’s a lot of people. And according to experts, 25% to 70% of those prescriptions are unnecessary. Why? Because PPIs are easy to prescribe, easy to get, and patients feel better right away. Doctors don’t always ask, “Do you still need this?” Patients don’t always ask, “Can I stop?”

It’s also a money problem. In the U.S. alone, inappropriate PPI use costs about $12 billion a year. That’s billions spent on drugs that aren’t helping-and may be hurting.

Even though guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association say to use PPIs at the lowest dose for the shortest time, many doctors still write 30-day or 90-day scripts without follow-up. And patients, feeling better, assume it’s safe to keep going.

What You Can Do Today

If you’re on a PPI:

- Check how long you’ve been taking it. If it’s more than 8 weeks for mild GERD, talk to your doctor.

- Don’t stop suddenly. Plan a taper.

- Ask if you really need it. Is it for diagnosed GERD? An ulcer? Or just occasional heartburn?

- Try lifestyle changes first. Eat earlier. Avoid triggers. Lose weight if needed.

- Ask about checking your magnesium and B12 levels if you’ve been on it over a year.

- Never use OTC PPIs longer than 14 days without talking to a doctor.

PPIs are powerful tools. But like any powerful tool, they’re not meant to be left on all the time. The goal isn’t to avoid them completely-it’s to use them wisely. When you stop, you don’t just reduce risk-you reclaim your body’s natural balance.

Can I stop taking PPIs cold turkey?

No. Stopping suddenly can cause severe rebound acid reflux, with symptoms worse than before. Up to 80% of long-term users experience this. Always taper slowly under medical guidance-reduce the dose gradually, then switch to on-demand use before stopping completely.

How long is too long to be on a PPI?

For most conditions like mild GERD or heartburn, 4 to 8 weeks is enough. If you still need it after that, your doctor should reassess. Long-term use-defined as more than 3 months-should only continue if there’s a clear medical need, like healing severe esophagitis or preventing ulcers from NSAIDs. Regular check-ins every 6 to 12 months are recommended.

Do PPIs cause kidney disease?

PPIs can cause acute interstitial nephritis, a rare but serious kidney inflammation, especially within the first year of use. While some studies suggest a link to chronic kidney disease, the evidence isn’t strong enough to say PPIs directly cause it. Still, doctors monitor kidney function in long-term users, especially those with other risk factors like diabetes or high blood pressure.

Are over-the-counter PPIs safer than prescription ones?

No. OTC PPIs have the same active ingredients and risks as prescription versions. The only difference is the dose (usually 20mg) and the label warning: don’t use for more than 14 days without talking to a doctor. Many people ignore this and use them daily for months or years, increasing their risk of side effects like low magnesium, B12 deficiency, and infections.

What are the alternatives to PPIs?

For occasional heartburn, antacids like Tums or H2 blockers like famotidine (Pepcid) are safer short-term options. For chronic GERD, lifestyle changes-losing weight, avoiding late meals, cutting caffeine and alcohol-can be very effective. In some cases, surgery like fundoplication may be considered. Newer drugs called P-CABs, like vonoprazan, are being studied and may offer similar relief with fewer long-term risks, but they’re not yet widely available.

Comments

So let me get this straight-we’re paying billions so people can avoid eating pizza at midnight, but the real solution is just not being lazy? Brilliant. I’ll start charging my patients a fee for not being idiots.

Man I was on PPIs for 3 years straight after my ulcer. Didn’t realize I was basically starving my body of B12 until I started getting tingles in my hands. Doc finally said ‘stop’ and I switched to famotidine on demand. Life changed. 🙌

My abuela took Tums for heartburn for 50 years. Never needed a pill. Just stopped eating fried stuff after 8pm and slept with three pillows. The real medicine is discipline, not chemistry.

It is an undeniable fact that the pharmaceutical industry has engineered a systemic dependency on proton pump inhibitors through deliberate obfuscation of long-term risks, thereby exploiting the medical ignorance of the general populace and maximizing profit margins at the expense of public health. This is not medicine-it is corporate malfeasance.

Wait, so if I’ve been on omeprazole for 5 years because I ‘felt better,’ but never had an endoscopy… am I one of the 70% who don’t actually need it? That’s terrifying. I’ve been taking it since my ‘stress-induced heartburn’ in college. Guess I’ve got some questions for my GI doc.

Stop cold turkey = bad. Taper slow. Check B12. Try H2 blockers. Lifestyle first. Doc visit needed.

People think they’re invincible until their kidneys start failing or their bones turn to dust. You take PPIs like candy because you’re too lazy to change your diet, and now you’re surprised when your body rebels? You didn’t get sick because of the drug-you got sick because you ignored every warning sign and treated your stomach like a trash can. You’re not a patient. You’re a cautionary tale waiting to happen.

It’s funny how we treat medicine like a switch instead of a conversation. We turn on acid suppression and forget that our bodies were designed to manage acid, not surrender to it. Maybe the real question isn’t whether to stop PPIs-but why we let them become our default solution in the first place.

They don’t want you to stop PPIs because the FDA, Big Pharma, and the AMA are all in cahoots with the hospital-industrial complex. The real danger is not the drug-it’s that they want you dependent so they can track your microbiome, sell your data, and eventually replace your stomach with a bio-chip. You think this is about health? It’s about control.

Thank you for this thoughtful and well-researched article. 🙏 I have been on PPIs for 2 years and will schedule a tapering plan with my doctor next week. Your clarity has given me peace of mind and a path forward.

It’s important to distinguish between correlation and causation in the context of PPI-associated outcomes. The epidemiological data demonstrating associations with interstitial nephritis, hypomagnesemia, and C. diff infection are statistically significant, but confounding variables-including age, comorbidities, polypharmacy, and baseline gastrointestinal pathology-must be rigorously controlled for in longitudinal analyses. The FDA warnings, while prudent, do not establish direct etiological linkage in the absence of RCTs.

OMG I was literally just thinking about this last night! I’ve been on omeprazole since 2019 and thought I was ‘fine’-until I started feeling like a zombie from B12 deficiency. My nails were splitting, my brain felt foggy, and I thought I was just aging. Turns out I was just slowly dying from a pill. I’m tapering this week and eating more eggs and salmon. I’m so mad I didn’t know sooner!!

I’ve been on PPIs for 10 years and my doctor never said a word. Now I’m terrified I’ve ruined my kidneys, my bones, my brain-what if I already have cancer? I’m going to die because no one cared enough to tell me to stop. I’m not just mad-I’m devastated. I trusted them. Why didn’t they warn me?

My dad stopped PPIs cold turkey and ended up in ER with acid so bad he couldn’t swallow. Now he’s on a 3-month taper. Lesson learned: don’t be a hero. Listen to the doc.

Thank you for sharing this. I’ve been helping patients wean off PPIs for years and the most common fear is rebound. It’s real, but manageable. With patience and support, most people find balance without drugs. You’re not broken-you’re just out of rhythm.