When someone is diagnosed with Parkinsonism, the first question isn’t usually about medication-it’s about what comes next. How will daily life change? Will they still be able to walk, talk, or hold a cup of coffee? The truth is, Parkinsonism doesn’t hit hard all at once. It creeps in, changes slowly, and unfolds in stages. Knowing what to expect isn’t about fear-it’s about preparing, adapting, and keeping control for as long as possible.

Stage One: Subtle Signs You Might Ignore

This is the quiet beginning. Most people don’t realize anything’s wrong. Maybe one hand trembles slightly when at rest-just enough to notice when holding a phone. Or perhaps their arm doesn’t swing naturally when walking. A slight stiffness in the shoulder, a softer voice, or a face that looks less expressive. These aren’t dramatic. They’re easy to brush off as aging, stress, or fatigue.

At this stage, symptoms are usually only on one side of the body. A person can still work, drive, and do chores without help. But if you look closely, small changes are there: handwriting gets smaller, steps feel a little shorter, blinking feels less frequent. These aren’t just quirks. They’re early signals of dopamine loss in the brain’s basal ganglia, the area that controls smooth movement.

Doctors often don’t confirm Parkinsonism until later, because the signs are too mild. But if you notice these changes lasting more than a few weeks, it’s worth seeing a neurologist. Early detection doesn’t cure it-but it gives you time to build a plan.

Stage Two: Symptoms Spread, Daily Life Adjusts

Now the tremors, stiffness, and slowness show up on both sides of the body. Walking becomes more labored. Getting out of a chair takes effort. Facial expressions flatten even more-what’s called a "masked face." Speech gets quieter and more monotone. People start to notice. A partner might say, "You’ve been talking softer lately." A friend comments, "You don’t seem like yourself."

Balance is still okay, but fine motor skills suffer. Buttoning a shirt, tying shoelaces, or using utensils takes longer. Fatigue sets in faster. Sleep gets disrupted-not just from movement, but from restless legs or vivid dreams. Many people start experiencing constipation or a loss of smell at this point, too. These are non-motor symptoms, and they’re often ignored because they don’t look like "Parkinson’s."

Medication like levodopa usually starts here. It helps a lot at first. But it’s not magic. It doesn’t stop the disease. It just replaces the dopamine the brain is losing. People in this stage can still live independently, but they may need small changes: grab bars in the bathroom, slip-on shoes, voice amplifiers for phone calls.

Stage Three: The Turning Point

This is the midpoint. Balance starts to fail. A person might still stand on their own, but if you nudge them gently, they could fall. Falls become a real concern. Movements slow down even more-this is bradykinesia in full force. Getting dressed, cooking, or showering takes twice as long. Some people start needing help with daily tasks, even if they don’t want to admit it.

Medication effects become less predictable. The "on-off" phenomenon begins: one minute they’re moving fine, the next they’re frozen in place. This isn’t random-it’s the brain’s dopamine levels dropping between doses. Doctors may adjust timing or add other drugs like dopamine agonists or MAO-B inhibitors to smooth things out.

Non-motor symptoms grow too. Depression and anxiety are common. Memory lapses might appear. Some people develop orthostatic hypotension-dizziness when standing up. These aren’t just "in their head." They’re physical changes in the nervous system. Physical therapy becomes essential. Exercises that focus on balance, posture, and big movements (like tai chi or LSVT BIG) can slow decline and reduce fall risk.

Stage Four: Independence Begins to Fade

At this stage, most people can’t live alone safely. They may still stand or take a few steps with help, but walking unaided is risky. A walker or wheelchair is often needed. Tremors may lessen, but stiffness and slowness worsen. Swallowing becomes harder. Choking risks rise. Speech is often barely understandable. Caregivers are no longer optional-they’re necessary.

Medication still helps, but side effects get worse. Dyskinesia-uncontrolled, jerky movements-can appear as a side effect of long-term levodopa use. This is frustrating: the drug that helps movement now causes unwanted movement. Doctors may lower doses or try continuous delivery systems like Duopa (a gel pumped into the intestine) to keep levels steadier.

Non-motor symptoms dominate now. Cognitive changes are clearer: trouble planning, remembering names, following conversations. Some develop hallucinations or delusions. These aren’t signs of dementia yet, but they’re warning signs. Sleep problems, urinary incontinence, and severe constipation add to the burden. Home modifications become critical: ramps, stair lifts, automated lighting, voice-controlled devices.

Stage Five: The Most Advanced Phase

This is the stage most people fear. The person is wheelchair-bound or bedridden. They can’t stand or walk at all. Speech is often reduced to whispers or single words. Swallowing is so difficult that feeding tubes may be needed to prevent malnutrition and aspiration pneumonia. Care is full-time. Even turning over in bed requires help.

Medication becomes less effective. The body struggles to absorb or respond to drugs. At this point, deep brain stimulation (DBS) is no longer an option for most-it’s typically done earlier. The focus shifts to comfort: managing pain, preventing bedsores, keeping the airway clear, and maintaining dignity.

Non-motor symptoms are overwhelming. Dementia affects up to 80% of people in this stage. Hallucinations and delusions are common. Emotional swings, agitation, and withdrawal happen often. This isn’t just physical decline-it’s a complex neurological storm.

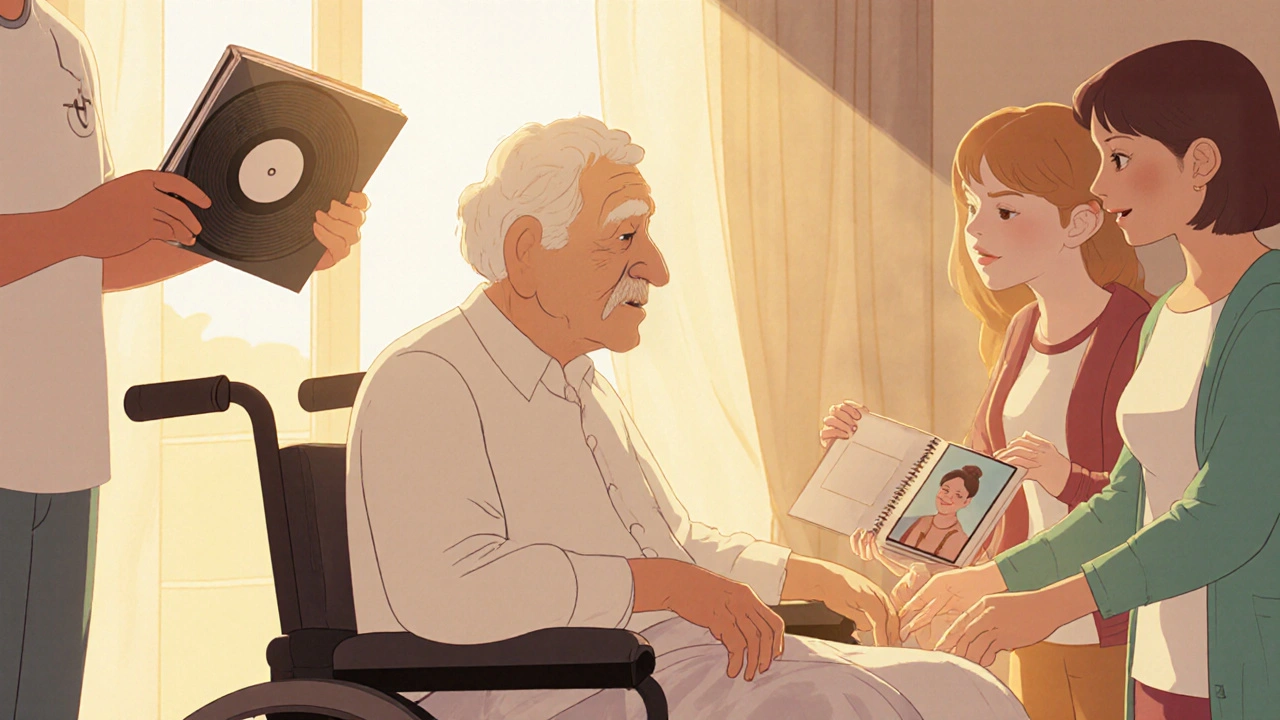

But even here, quality of life matters. Music therapy, gentle touch, familiar voices, and routines can bring calm. A warm blanket, a favorite song, or a family photo can mean more than any drug. Palliative care teams step in-not to end life, but to make it as peaceful as possible.

What Doesn’t Change: You’re Still You

It’s easy to think Parkinsonism takes the person away. But it doesn’t. The mind, the humor, the love, the memories-they’re still there. Many people with advanced Parkinsonism can still enjoy a meal with family, laugh at a joke, or feel the sun on their face. The disease changes the body, not the soul.

That’s why support matters. Not just medical support, but emotional, social, and practical. Support groups, online communities, and caregiver training programs exist for a reason. People with Parkinsonism and their families don’t need pity. They need connection, understanding, and tools to keep living.

What You Can Do Now

Even if you’re in Stage One, here’s what helps:

- Get moving: Regular exercise-walking, swimming, cycling-slows motor decline.

- Speak up: If your voice is fading, see a speech therapist. LSVT LOUD therapy works.

- Watch your diet: High fiber, plenty of water, and protein timing (separate from meds) help with digestion and medication absorption.

- Plan ahead: Talk about future care. Power of attorney, advance directives, and home safety checks aren’t morbid-they’re smart.

- Find your team: A neurologist who specializes in movement disorders, a physiotherapist, an occupational therapist, and a social worker can make all the difference.

There’s no cure yet. But Parkinsonism isn’t a death sentence. It’s a journey with twists, but also moments of joy, connection, and quiet strength. The goal isn’t to stop the progression-it’s to live fully through every stage.

Can Parkinsonism be cured?

No, there is no cure for Parkinsonism today. But treatments like levodopa, deep brain stimulation, and physical therapy can manage symptoms effectively for many years. Research into new therapies-including gene therapy and neuroprotective drugs-is ongoing, and clinical trials are expanding.

Is Parkinsonism the same as Parkinson’s disease?

Parkinsonism is a broader term that includes Parkinson’s disease but also other conditions that cause similar symptoms, like drug-induced parkinsonism, multiple system atrophy, or progressive supranuclear palsy. Parkinson’s disease is the most common cause, but not the only one. A neurologist can help distinguish between them.

How fast does Parkinsonism progress?

Progression varies widely. Some people move through stages in 5-10 years. Others stay stable for 20 years or more. Age at diagnosis, overall health, lifestyle, and access to care all play a role. There’s no set timeline-each person’s journey is unique.

Can diet affect Parkinsonism symptoms?

Yes. High-protein meals can interfere with levodopa absorption, so timing meals around medication helps. Fiber and fluids reduce constipation, a common issue. Some evidence suggests the Mediterranean diet-rich in fruits, vegetables, olive oil, and fish-may support brain health. Avoiding processed foods and sugar also helps with energy and inflammation.

When should I consider a care facility?

Consider it when safety is at risk: frequent falls, inability to swallow safely, wandering, or when caregivers are overwhelmed or exhausted. Memory care units or specialized Parkinson’s facilities offer trained staff, adapted environments, and 24/7 support. It’s not failure-it’s choosing quality of life for both the person and their family.

Comments

Man, this post is a masterclass in clarity. I’ve been working with Parkinson’s patients for over a decade, and honestly? Most docs skip the *human* part-the little things like how a person still loves their morning coffee even if they spill it now, or how their laugh hasn’t changed even when their voice is a whisper. The dopamine loss? Yeah, it’s biological. But the soul? That’s still there, dancing in the cracks. Keep talking like this. People need to hear it.

meh. i seen this before. all this stage stuff is just fear porn. people get scared and buy apps and supplements. real talk? just move. walk. dont sit around reading essays. its not that complicated.

This is the kind of info that actually helps.

Just wanted to say thank you for writing this. My mom’s in stage three and I’ve been drowning in info that’s either too clinical or too scary. This? This felt like a friend sitting with me over coffee. The part about LSVT BIG? We started that last month. She’s still shaky, but she’s smiling more. And yeah, the ‘you’re still you’ part? That’s the one I printed and taped to the fridge. We’re not giving up. Just adjusting.

why do americans always make everything so dramatic its just a disease you dont need 5 stages and poetry about the soul just take your meds and dont be lazy

Hey Ram tech, I get where you’re coming from-action matters. But for a lot of people, understanding *how* the disease works helps them move better. It’s not about fear-it’s about strategy. Like knowing why your meds don’t work after a big steak dinner? That’s power. You don’t need to read a novel, but a little context? It turns panic into planning. And planning saves dignity.

Okay but can we talk about how the whole ‘non-motor symptoms’ section is basically the secret sauce? Like, people don’t realize that if your anosmia hits before tremors, you’ve got a 7-year window to prep. And the constipation? That’s not ‘just aging’-it’s enteric nervous system decay. We need more neuro-gastro stuff in mainstream docs. Also, dopamine agonists are a nightmare if you’re a control freak-I turned into a compulsive gambler for 18 months. No one warned me.

kim pu i had that too with the gambling thing. my dad went from quiet guy to betting on horses at 2am. we thought he was cheating on mom. turns out it was the meds. no one told us it could do that. so much of this is hidden. thank you for saying it out loud. i feel less alone now.

this is so good 😊 my uncle in india has parkinson's and no one here talks about stages. we just say he's getting old. your post made me call him. he cried. i think he finally felt seen. 🙏