When your kidneys start leaking protein into your urine, it’s not just a lab result-it’s your body screaming for help. In people with diabetes, this leak is often the first sign of diabetic kidney disease (DKD), a slow, silent killer that can turn manageable diabetes into kidney failure. The key? Catching it early through a simple urine test called UACR-and acting fast with tight control of blood sugar and blood pressure.

What Is Albuminuria, and Why Does It Matter?

Albuminuria means your urine has too much albumin, a protein your kidneys normally keep in your blood. When your kidneys are healthy, they act like fine sieves, keeping proteins inside and letting waste out. But high blood sugar over time damages those sieves. Even small amounts of albumin in the urine-30 mg/g or more-are a red flag.

Doctors now classify albuminuria in three clear stages:

- Normal: Less than 30 mg/g (UACR)

- Moderately increased: 30-300 mg/g (formerly called microalbuminuria)

- Severely increased: Over 300 mg/g (formerly macroalbuminuria)

The term "microalbuminuria" was dropped in 2012 because it misled people into thinking small amounts were harmless. They’re not. Any albumin above 30 mg/g means your kidneys are already damaged. And the higher the number, the faster things can spiral.

A 2021 study of over 128,000 diabetic patients showed that those with severely increased albuminuria had a 73% higher risk of dying from any cause-and an 81% higher risk of dying from heart disease-compared to those with normal levels. This isn’t just about kidneys. It’s about your whole body.

How Do You Know If You Have Albuminuria?

The test is simple: a urine sample, usually a spot check, measured against creatinine to give you the UACR ratio. No fasting. No special prep. Just pee in a cup.

But here’s the catch: one high reading doesn’t mean you have DKD. Albumin levels can spike temporarily from things like:

- Strenuous exercise in the last 24 hours

- Feeling sick with a fever or infection

- Severe high blood pressure (over 180/110)

- Very high blood sugar (above 300 mg/dL)

- Menstruation

That’s why guidelines require two out of three abnormal tests within 3 to 6 months before confirming diagnosis. If your first test is high, don’t panic. Get retested after you’re feeling better and your blood sugar is stable.

Screening is non-negotiable. The American Diabetes Association says everyone with type 2 diabetes should get tested at diagnosis. For type 1 diabetes, start testing after 5 years. And if you’re already diagnosed with DKD, check every 3 to 4 months after starting treatment.

Tight Control Isn’t Just a Buzzword-It’s Life-Saving

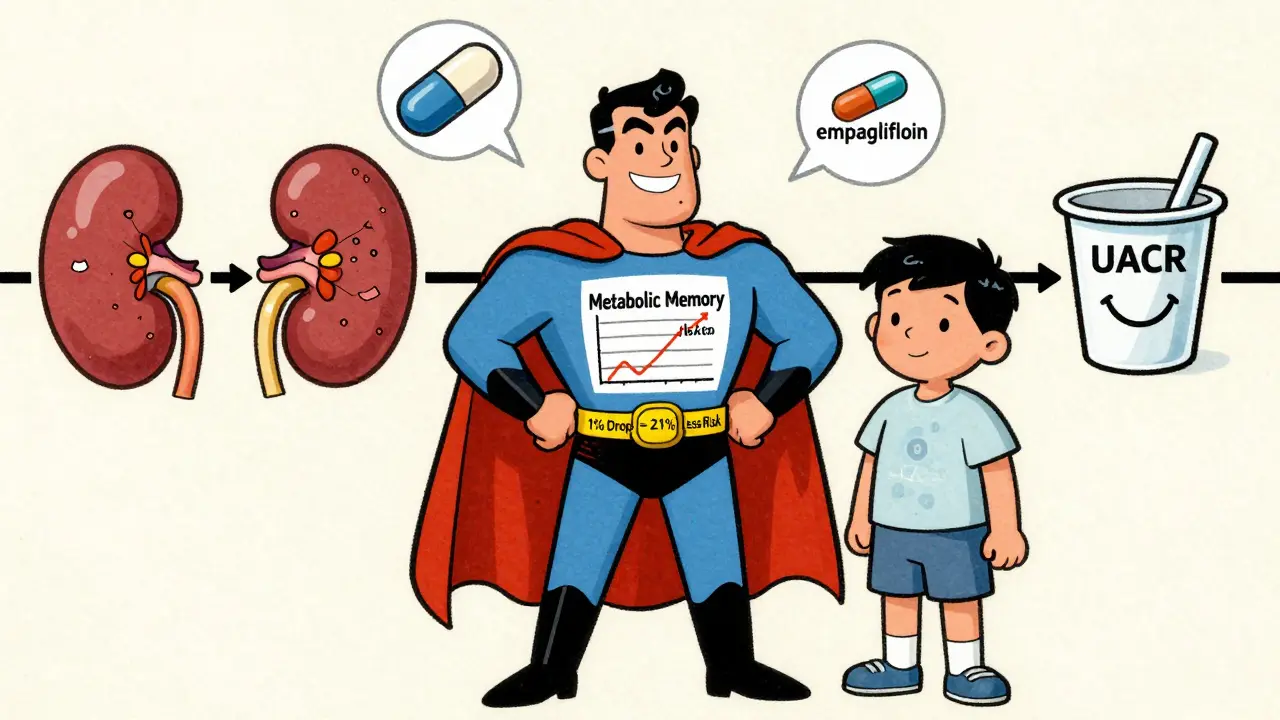

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) and its follow-up EDIC study changed everything. In the 1990s, researchers split type 1 diabetes patients into two groups: one with tight control (HbA1c under 7%) and one with conventional control (HbA1c around 9%). After 10 years, the tightly controlled group had 39% less microalbuminuria and 54% less proteinuria.

Even more shocking? Those benefits lasted for decades. The group that had tight control in their 20s and 30s still had better kidney function 30 years later. That’s called "metabolic memory"-your body remembers what you did to it years ago.

For type 2 diabetes, the UKPDS study found that every 1% drop in HbA1c lowered DKD risk by 21%. That’s not a small win. That’s the difference between keeping your kidneys for life or ending up on dialysis.

Current guidelines recommend an HbA1c under 7% for most people with diabetes. But if you’re younger, have had diabetes for less than 10 years, and aren’t at high risk for low blood sugar, aiming for under 6.5% can give you even better protection.

Blood Pressure: The Other Half of the Battle

High blood pressure doesn’t just hurt your heart-it crushes your kidneys. In DKD, the two go hand in hand. When your kidneys are damaged, they can’t regulate blood pressure properly, which makes the damage worse.

For years, doctors aimed for under 130/80 mmHg. But newer data from the SPRINT trial showed that pushing systolic pressure below 120 mmHg reduced albuminuria by 39%. Sounds great, right? Except it also increased the risk of acute kidney injury in 1 out of every 47 patients.

That’s why the American Diabetes Association now recommends under 140/90 mmHg for most people with DKD. But if you have severe albuminuria (over 300 mg/g) and no other major health issues, your doctor might consider aiming lower-around 120/80-after careful discussion.

The key is not just lowering pressure, but using the right drugs. ACE inhibitors and ARBs (like lisinopril or losartan) don’t just lower blood pressure-they directly protect the kidneys by reducing pressure inside the filtering units. The IRMA-2 trial showed that losartan at 100 mg/day cut progression from micro- to macroalbuminuria by 53%.

And here’s the rule: titrate to the maximum tolerated dose. Don’t stop at the starting dose. If you can handle it, go higher. That’s where the real protection kicks in.

New Drugs Are Changing the Game

For years, ACE inhibitors and ARBs were the only tools we had. Now, we have two game-changers:

- SGLT2 inhibitors (like empagliflozin, dapagliflozin): Originally diabetes drugs, they now have proven kidney protection. The EMPA-KIDNEY trial showed they reduced the risk of kidney failure or death by 28% in patients with UACR over 200 mg/g-even when used alongside ACE/ARBs.

- Finerenone: A newer mineralocorticoid receptor blocker that doesn’t cause the same potassium spikes as older drugs. In trials, it cut albuminuria by 32% in just 4 months and slowed kidney decline by 23% over 3 years.

These aren’t add-ons anymore. They’re first-line. If you have DKD with albuminuria over 30 mg/g, you should be on an SGLT2 inhibitor. If you’re already on an ACE/ARB and still have albuminuria, finerenone should be considered.

Yet, real-world data shows only 28.7% of patients with DKD are getting all three recommended therapies: ACE/ARB, SGLT2 inhibitor, and finerenone when needed. Why? Cost, access, lack of awareness, and fragmented care.

Why So Many People Are Falling Through the Cracks

Here’s the ugly truth: even though we know exactly what to do, most people aren’t doing it.

NHANES data from 2017-2018 showed:

- Only 52.5% of adults with diabetes hit HbA1c under 7%

- Only 56.9% control blood pressure under 140/90

- Just 12.2% hit all three targets: blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol

And screening? Only 58-65% of clinics in the U.S. regularly test UACR, even though the ADA calls it a Class A recommendation-the highest level of evidence. Why?

- 78% of clinics lack automated EHR reminders

- 23% of patients don’t return for follow-up urine tests

- 41% of primary care providers don’t fully understand how predictive albuminuria is

But some places are fixing it. Clinics using point-of-care urine testers cut follow-up loss by 37%. Pharmacist-led teams that titrate medications to max doses got 89% of patients to optimal therapy. These aren’t magic. They’re systems.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you have diabetes, here’s your action plan:

- Get your UACR tested annually-or every 3-4 months if you’ve been diagnosed with albuminuria.

- Ask your doctor: "Is my albuminuria level trending up or down?" Don’t just accept a number-ask what it means for your future.

- Get your HbA1c under 7% (or under 6.5% if you’re a good candidate).

- Keep blood pressure under 140/90-and make sure you’re on an ACE inhibitor or ARB.

- Ask about SGLT2 inhibitors (like empagliflozin) and whether finerenone is right for you.

- Don’t skip follow-ups. One missed urine test could mean a year of undetected damage.

Diabetic kidney disease doesn’t happen overnight. But it doesn’t stop either. Left unchecked, it leads to dialysis, transplant, heart attacks, and early death. The good news? You have more power than you think.

Every 1% drop in HbA1c. Every 5 mmHg lower in blood pressure. Every time you take your pill. Every urine test you complete. These aren’t small things. They’re the difference between losing your kidneys-and keeping them.

The science is clear. The tools exist. The question now is: are you ready to act before it’s too late?

What is UACR, and why is it the best test for diabetic kidney disease?

UACR stands for Urine Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio. It measures how much albumin-a type of protein-is leaking into your urine compared to creatinine, a waste product. It’s the best early test because albuminuria shows up before your kidney function drops. You don’t need a 24-hour collection; a simple spot urine sample gives accurate results. Levels under 30 mg/g are normal. Anything above that signals kidney damage, even if your eGFR is still normal.

Can albuminuria go away if I get my blood sugar under control?

Yes, in many cases. Studies show that with tight glycemic control and blood pressure management, up to 50% of people with moderately increased albuminuria (30-300 mg/g) can return to normal levels. The earlier you act, the better your chances. Once you reach severely increased albuminuria (over 300 mg/g), reversal becomes much harder, but slowing or stopping progression is still very possible with the right medications.

Do I need to take medication if my albuminuria is only mildly elevated?

Even mild albuminuria (30-300 mg/g) means your kidneys are already damaged. Medication isn’t optional at this stage-it’s preventive. ACE inhibitors or ARBs are recommended even if your blood pressure is normal. These drugs protect your kidneys directly, not just by lowering pressure. Waiting until your kidneys start failing is too late. Early intervention is what keeps you off dialysis.

Why aren’t more doctors testing for albuminuria regularly?

Many primary care clinics don’t have automated reminders in their electronic health records, so testing gets missed. Some providers still think "microalbuminuria" isn’t serious, or they assume patients will come back for follow-up. Others worry about cost or don’t know how to interpret results. But the evidence is overwhelming: annual UACR testing is a Class A recommendation from the ADA and KDIGO. If your doctor isn’t ordering it, ask why.

Are SGLT2 inhibitors and finerenone covered by insurance?

Coverage varies, but most major insurance plans in the U.S. cover SGLT2 inhibitors and finerenone for diabetic kidney disease, especially when prescribed for kidney protection-not just blood sugar. Some require prior authorization. If your doctor says it’s not covered, ask them to appeal using the 2023 EMPA-KIDNEY and FIDELIO-DKD trial data, which are now standard in KDIGO guidelines. Patient assistance programs from drug manufacturers are also available.

Comments

Been living with type 2 for 12 years. My UACR was 210 last year-scared the hell out of me. Started on empagliflozin, dropped my HbA1c from 8.2 to 6.3, and now my albumin’s down to 45. No magic, just consistency. If you’re reading this and still ignoring your urine test? You’re playing Russian roulette with your kidneys.

It is profoundly concerning that the medical community continues to treat diabetic kidney disease as a secondary concern rather than a primary, life-threatening pathology. The data presented here is not merely suggestive-it is definitive. The failure of primary care systems to implement routine UACR screening constitutes a systemic dereliction of duty. One cannot ethically justify the omission of a Class A recommendation under any circumstance. This is not negligence-it is malpractice by omission.

okay but like… i just got my UACR back and it’s 89 😭 i’m not even mad, just… disappointed in myself? i’ve been eating keto for 3 months but my BP is still 145/92 😩 my doctor said ‘it’s not bad yet’ but i know it is. anyone else feel like your body’s betraying you?? 🥺 i’m starting losartan next week and i’m gonna cry if my next test is normal. 💪❤️

While the clinical evidence supporting early intervention in diabetic kidney disease is robust, it is equally critical to recognize the psychosocial barriers to adherence. Many patients experience fatigue, denial, or learned helplessness-emotional states that are rarely addressed in clinical guidelines. A multidisciplinary approach incorporating behavioral health support is not optional; it is foundational to sustainable outcomes.

Let’s be honest: the entire paradigm of ‘tight control’ is built on a fallacy. You can’t ‘control’ a metabolic disease with pills and arbitrary HbA1c targets. The real issue is that we’ve outsourced responsibility to pharmaceutical companies and lab tests while ignoring the root cause: systemic inflammation from ultra-processed food and chronic stress. SGLT2 inhibitors? Fine. But if you’re still eating industrial seed oils and drinking diet soda while taking them, you’re just delaying the inevitable. The body doesn’t care about your UACR number-it cares about what you put in your mouth and how you treat your nervous system. This is medicine as distraction.

Here’s the truth no one wants to admit: 70% of people with albuminuria don’t even know what UACR stands for. And the doctors? Half of them don’t know how to interpret it correctly. You get a result of 120 mg/g? ‘Oh, that’s just microalbuminuria.’ No. It’s kidney damage. Period. The system is broken because we treat numbers like they’re suggestions, not warnings. And then we wonder why dialysis rates are rising. It’s not a medical failure-it’s a cultural one.

I’ve been a diabetes educator for 18 years, and I’ve seen people turn things around-even when they’re way past ‘micro.’ One patient, 62, had UACR at 420, eGFR at 45. She was told she’d be on dialysis in 3 years. She started on losartan, empagliflozin, cut out soda, walked 30 minutes every day, and got her HbA1c under 6.5. Five years later? UACR at 55, eGFR still at 45-but stable. She didn’t reverse it. She stopped the clock. And that’s a win. You don’t need perfection. You need persistence. One pill. One walk. One test. One day at a time. It adds up.

Wait, so you’re telling me I need to take THREE drugs just because my urine has a little protein? I’ve been on metformin for 8 years and my A1c is 6.8. I don’t need finerenone. I don’t need SGLT2 inhibitors. I’m not a lab rat. This is just Big Pharma pushing more pills. If I eat clean and exercise, why do I need more meds? You’re turning diabetes into a pharmaceutical empire.