Why Low Blood Sugar Is a Bigger Danger for Seniors with Diabetes

When you’re over 65 and managing diabetes, the biggest threat isn’t high blood sugar-it’s low blood sugar. A blood glucose reading below 70 mg/dL might seem minor, but for older adults, it can mean a fall, a trip to the ER, or worse. Seniors are two to three times more likely than younger people to have dangerous hypoglycemia episodes. Why? Their bodies don’t respond the same way. Kidneys slow down, liver glycogen stores drop, and the hormones that normally kick in to raise blood sugar-like glucagon and epinephrine-don’t work as well. Even a mild dip can cause dizziness, confusion, or fainting. And once you fall, the risks multiply: broken hips, head injuries, long hospital stays, and higher chances of dying within a year.

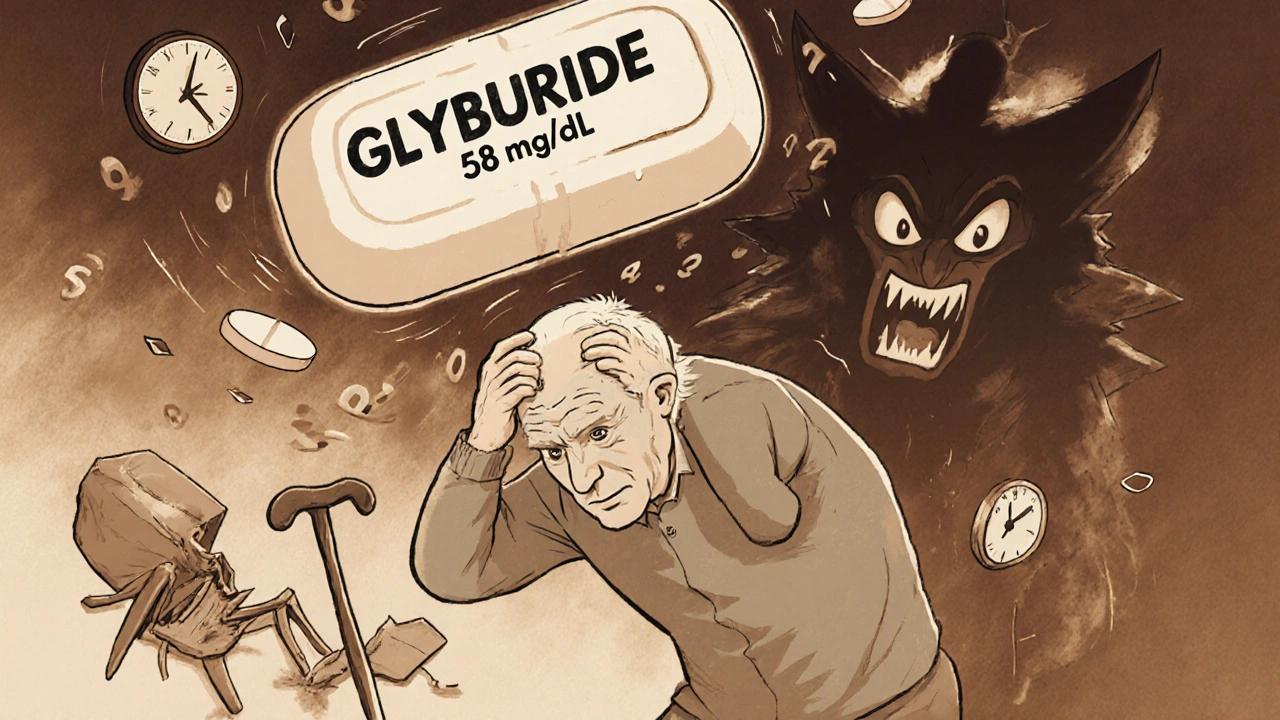

Medications That Put Seniors at Highest Risk

Not all diabetes drugs are created equal when it comes to safety in older adults. The biggest red flag? Glyburide. This sulfonylurea is still prescribed to seniors, even though it’s on the American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria list of medications to avoid in older adults. Why? It sticks around in the body too long. It’s cleared by the kidneys, and as kidney function declines with age, glyburide builds up. Studies show nearly 40% of seniors on glyburide have at least one low blood sugar episode per year. Some end up in the hospital. One 82-year-old man in Ohio had three falls in six months-each linked to nighttime lows from glyburide. His doctor switched him to linagliptin, and within weeks, his blood sugar stayed steady between 90 and 140 mg/dL.

Other sulfonylureas like glipizide and glimepiride are slightly safer, but still risky. Glipizide has a shorter half-life, so it doesn’t linger as long. Still, it can cause lows, especially if meals are skipped or activity levels change. Insulin is another major culprit. Seniors on insulin have a 30% higher chance of falling due to sudden dizziness or weakness. Many don’t realize their symptoms are from low sugar until it’s too late.

The Safer Alternatives: What Doctors Should Be Prescribing

There are much safer options that don’t trigger low blood sugar. The first group is DPP-4 inhibitors: sitagliptin (Januvia), linagliptin (Tradjenta), and saxagliptin (Onglyza). These work by boosting the body’s own insulin only when blood sugar is high. They rarely cause hypoglycemia on their own-studies show rates of just 2% to 5%, compared to 15% to 40% with sulfonylureas. Linagliptin is especially good for seniors because it’s cleared through the liver, not the kidneys. That means no dose adjustments, even if kidney function is low.

Another safe choice? SGLT2 inhibitors like empagliflozin (Jardiance) and dapagliflozin (Farxiga). These help the kidneys flush out extra sugar through urine. They don’t cause low blood sugar unless combined with insulin or sulfonylureas. In clinical trials, only 4.5% of seniors on Jardiance had hypoglycemia, compared to 13.8% on placebo. That’s a huge win.

And then there’s metformin. It’s usually the first-line drug for type 2 diabetes, but in seniors, it needs careful handling. It’s safe if kidneys are working well. But if creatinine clearance is below 30 mL/min, or if the person is over 80, many doctors avoid it. Why? Risk of lactic acidosis, though rare, is higher in older adults with poor kidney function.

What About Newer Drugs? Tirzepatide and Beyond

In 2022, the FDA approved tirzepatide (Mounjaro), a new injectable that combines GLP-1 and GIP receptor agonism. In trials with seniors, hypoglycemia rates were only 1.8%-far lower than insulin glargine’s 12.4%. It’s not yet widely used in elderly patients due to cost and side effects like nausea, but it’s a promising option for those who need stronger control without the danger of lows.

Even more exciting? The next generation of insulin. Researchers are developing "smart insulin" that activates only when blood sugar rises above a certain level. Early trials are showing zero hypoglycemia in elderly participants. These aren’t on the market yet, but Phase 2 trials are actively recruiting seniors. If successful, they could change everything.

How to Spot a Low Blood Sugar Episode Early

Seniors often don’t feel the classic warning signs. Sweating, shaking, and a fast heartbeat? Those can be missing. Instead, they might just feel tired, confused, or unusually irritable. One 78-year-old woman thought she was getting dementia-until her daughter noticed her blood sugar was 58 mg/dL during one of her "foggy" spells. That’s when they switched her from glyburide to sitagliptin.

Here’s what to watch for in older adults:

- Headache or dizziness

- Weakness or feeling shaky

- Confusion or trouble speaking

- Sudden mood changes-irritability or crying

- Slurred speech or clumsiness

- Unexplained fatigue or sleepiness

These aren’t just "getting older" symptoms. They’re red flags. If your parent or loved one shows any of these, check their blood sugar right away. Don’t wait. Treat it with 15 grams of fast-acting sugar-glucose tablets, juice, or candy-and recheck in 15 minutes.

Monitoring and Technology That Actually Help

Traditional fingerstick checks aren’t enough. Seniors often forget to test, or they’re afraid of pricking their fingers. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) like Dexcom G7 or Freestyle Libre 3 are game-changers. They track sugar levels 24/7 and send alerts to phones or smartwatches when levels drop too low. A 2021 study found seniors using CGMs had 65% fewer hypoglycemic events than those using fingersticks. One woman in Florida started using Libre after two ER visits for low blood sugar. She says, "Now I sleep through the night without worrying I’ll wake up on the floor."

CGMs are covered by Medicare for many seniors with diabetes, especially those on insulin or with a history of lows. Ask your doctor about a prescription. It’s not just a gadget-it’s a safety net.

Medication Reviews and Avoiding Dangerous Mixes

Most seniors with diabetes take more than five medications. That’s called polypharmacy. And it’s a recipe for trouble. Beta-blockers for high blood pressure can hide the symptoms of low blood sugar-no fast heartbeat, no shaking. NSAIDs like ibuprofen can make sulfonylureas stronger, pushing blood sugar down further. Even some antibiotics and antifungals can interact.

That’s why a full medication review every 3 to 6 months is non-negotiable. Pharmacists can spot dangerous combinations. The STOPP/START criteria-a tool used by geriatric specialists-helps identify which drugs should be stopped and which are missing. One study showed using this tool reduced hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations by 32% in seniors.

Ask your doctor: "Is any of my medication making me more likely to have low blood sugar?" If you’re on glyburide, ask if it can be switched. If you’re on insulin, ask if a basal insulin like glargine or degludec is the best option-or if a GLP-1 agonist might be safer.

Setting Realistic Blood Sugar Goals

Doctors used to push for HbA1c below 7%. For seniors, that’s often too aggressive. The American Diabetes Association now recommends personalized targets:

- 7.0%-7.5% for healthy seniors with few other health problems

- 7.5%-8.0% for those with moderate health issues

- Up to 8.5% for frail seniors or those with dementia, heart failure, or multiple chronic conditions

Why? Because chasing a lower number increases hypoglycemia risk-and that risk outweighs the benefits. The goal isn’t perfect numbers. It’s staying safe, staying active, and avoiding hospital visits. One study found seniors with HbA1c around 8.0% had fewer falls, fewer ER trips, and lived longer than those pushed to 6.8%.

What Families and Caregivers Can Do

You don’t need to be a doctor to help. Learn the signs of low blood sugar. Keep glucose tablets or juice boxes in the kitchen, car, and bedside drawer. Make sure your loved one eats regularly-even if they’re not hungry. Skip a meal? Check their sugar. Change their meds? Watch closely for the first two weeks. Talk to their pharmacist. Ask if their meds are on the Beers Criteria list. If you’re worried, say something. Many seniors won’t admit they’re feeling off because they don’t want to be seen as a burden.

And if your parent has had even one hypoglycemia episode in the past year, push for a medication review. Don’t wait for the next appointment. Call the doctor. Ask for a referral to a geriatric pharmacist. This isn’t just about diabetes-it’s about keeping someone independent, safe, and alive.

What diabetes meds should seniors avoid?

Seniors should avoid glyburide (a sulfonylurea) because it stays in the body too long and causes dangerous low blood sugar episodes. Other high-risk medications include long-acting insulin and, in some cases, glipizide if kidney function is poor. The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria explicitly lists glyburide as a medication to avoid in older adults due to its high hypoglycemia risk.

Is metformin safe for elderly patients?

Metformin is generally safe for seniors with healthy kidneys, but it’s often avoided in those over 80 or with reduced kidney function (creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min). The risk of lactic acidosis, though rare, increases with poor kidney function. Doctors usually check kidney function before prescribing and may reduce the dose or stop it if levels decline.

Can DPP-4 inhibitors cause low blood sugar?

DPP-4 inhibitors like sitagliptin, linagliptin, and saxagliptin rarely cause low blood sugar when taken alone. They only boost insulin when blood sugar is high, so they don’t push it too low. Hypoglycemia rates are only 2% to 5% with these drugs, compared to 15% to 40% with sulfonylureas. They’re considered among the safest oral options for seniors.

Should seniors use continuous glucose monitors (CGMs)?

Yes. CGMs like Freestyle Libre or Dexcom G7 are highly recommended for seniors, especially those with a history of hypoglycemia or on insulin. Studies show CGM users over 65 have 65% fewer low blood sugar events than those using fingersticks. They provide real-time alerts and reduce anxiety. Medicare often covers them for seniors who meet criteria, such as having had a prior severe hypoglycemia episode.

What’s the safest HbA1c target for an elderly diabetic?

The safest HbA1c target depends on health status. For healthy seniors, aim for 7.0%-7.5%. For those with multiple health issues, 7.5%-8.0% is better. For frail seniors or those with dementia or heart failure, up to 8.5% is acceptable. The goal isn’t perfection-it’s avoiding dangerous lows. Research shows seniors with HbA1c around 8.0% live longer and have fewer falls than those pushed to 6.8%.

Comments

Glyburide is a death sentence for seniors. I've seen it firsthand. Kidneys slow down, but doctors keep prescribing it like it's 1995. Time to stop pretending we're treating diabetes like it's a young person's disease.

Linagliptin? Now that's the move. Liver clearance = no dose adjustments. Why isn't this standard?

My grandma switched from glyburide to sitagliptin last year. No more falls. No more ER trips. She even started gardening again. Why do docs wait until someone breaks a hip?

Let’s be real-this post is just Big Pharma’s marketing brochure dressed up as medical advice. DPP-4 inhibitors cost 10x more than glyburide. Of course they’re ‘safer.’ They’re also unaffordable for 80% of seniors on fixed incomes.

I’m from rural Texas. My uncle was on glyburide for 12 years. His doctor never mentioned Beers Criteria. When he fell and broke his hip, the hospital pharmacist was the one who finally said, 'This med is killing him.'

Doctors don’t know geriatrics. Pharmacists do. We need geriatric pharmacists in every clinic. Not optional. Mandatory.

This is so important. My mom had two scary lows last winter. We didn’t know what was happening until we read this. We asked her doctor to switch her meds and got her a Libre. She sleeps better now. Thank you for writing this.

The assertion that metformin is unsafe in seniors over 80 is misleading. The risk of lactic acidosis is statistically negligible when kidney function is monitored appropriately. Discontinuing metformin without cause exposes patients to unnecessary hyperglycemia, which carries its own risks-including microvascular complications and increased mortality. Evidence-based medicine demands nuance, not blanket avoidance.

CGMs? Pfft. My aunt got one and said it beeps all night. She hates it. She says it’s just a fancy way to make people paranoid. Maybe we should just let old folks die how they wanna die instead of turning their lives into a medical alarm system.

You think this is about medicine? Nah. It’s about the pharmaceutical industry pushing expensive drugs to replace cheap ones. Glyburide costs $4. CGMs cost $1000. Who profits? Not the patient. Not Medicare. The shareholders. You’re being played.

I’m a nurse. I’ve seen this over and over. Seniors get put on insulin because it’s easy. Doctors don’t want to think. They don’t want to adjust. They don’t want to explain. So they just write ‘insulin 10 units’ and call it a day. Then the patient gets dizzy at 3 a.m. and ends up in the ER. This isn’t medical care. It’s negligence dressed in a white coat.

The claim that HbA1c targets up to 8.5% are 'safe' for frail seniors is dangerously oversimplified. While avoiding hypoglycemia is critical, uncontrolled hyperglycemia accelerates cognitive decline, increases infection risk, and contributes to vascular dementia. A target of 8.0% is reasonable; 8.5% crosses into therapeutic abandonment.

It is imperative that we recognize the systemic failure in geriatric diabetes management. The current paradigm, which prioritizes cost-efficiency and convenience over individualized, patient-centered care, is ethically untenable. We must advocate for interdisciplinary teams that include geriatricians, pharmacists, dietitians, and social workers to holistically address the multifactorial nature of diabetes in aging populations. The goal is not merely to avoid hypoglycemia, but to preserve dignity, autonomy, and quality of life.

Wait-so smart insulin is in trials? And it’s zero hypoglycemia? That’s wild. Why isn’t this front-page news?