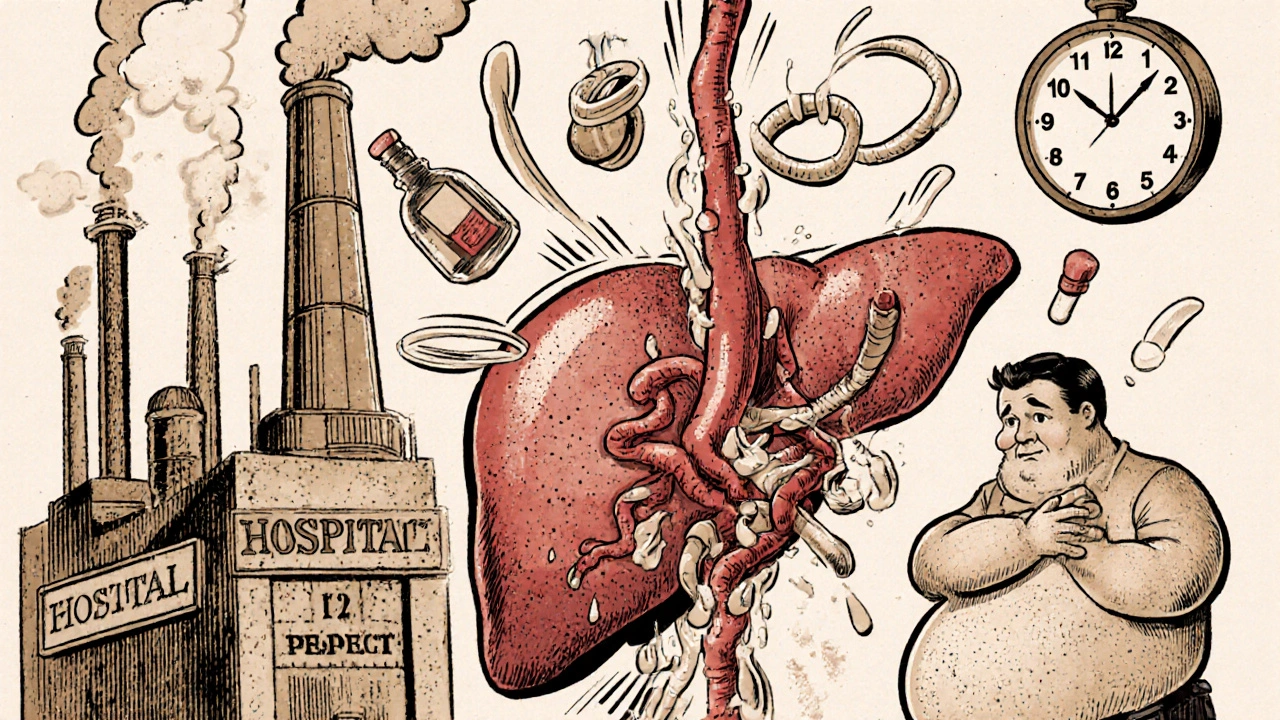

When your liver is damaged, blood doesn’t flow through it the way it should. That’s when portal hypertension kicks in - a dangerous rise in pressure inside the main vein that carries blood from your gut to your liver. It’s not a disease on its own, but a consequence of something worse: usually cirrhosis. And if left unchecked, it leads to life-threatening problems like bleeding varices, swollen bellies from fluid buildup, and brain fog from toxins your liver can’t filter. This isn’t rare. About 70% of people with cirrhosis develop it within five years. If you or someone you care about has liver disease, understanding how portal hypertension works - and how to stop its worst outcomes - could save a life.

What Exactly Is Portal Hypertension?

Portal hypertension means the pressure in the portal vein - the big blood vessel that brings nutrient-rich blood from your intestines to your liver - has climbed too high. Normal pressure? Between 5 and 10 mmHg. Once it hits 10 mmHg or higher, or if the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) exceeds 5 mmHg, you’ve crossed into portal hypertension. The HVPG is the gold standard measurement. It’s taken during a minor procedure where a catheter is inserted into a liver vein. But you don’t need to know the numbers to understand the danger. What matters is what happens when pressure builds up.Ninety percent of the time, this is caused by cirrhosis - scar tissue replacing healthy liver cells. That scar tissue blocks blood flow. The rest? Non-cirrhotic causes like blood clots in the portal vein, rare infections, or inherited conditions. But cirrhosis is the elephant in the room. And it’s growing. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), linked to obesity and diabetes, now causes nearly a quarter of all cirrhosis cases globally. That means more people are at risk than ever before.

Varices: The Silent Time Bomb

When blood can’t flow easily through the liver, it looks for other paths. It finds them - in the veins of your esophagus and stomach. These veins aren’t built for high pressure. They swell, stretch, and become varices. Think of them like bulging garden hoses. One tiny tear, and you’re bleeding internally. That’s not a slow leak - it’s a gusher. Half of all cirrhosis patients develop varices within ten years. And 5 to 15% of those with medium or large varices will bleed each year.The first sign? Often nothing. That’s why screening is critical. If you have cirrhosis, you need an endoscopy to check your esophagus. Once varices are found, treatment starts immediately. The go-to method? Endoscopic band ligation. A tiny rubber band is placed around the varix, cutting off its blood supply. It’s quick, minimally invasive, and cuts rebleeding risk from 60% down to 20-30%. Medications help too. Non-selective beta-blockers like propranolol lower portal pressure by slowing your heart and reducing blood flow. Taken daily, they can reduce first-time bleeding risk by nearly half.

But here’s the catch: even with treatment, 60% of patients who’ve bled once will bleed again within a year if they don’t stick to their full treatment plan. That’s why after a bleed, doctors combine banding with beta-blockers - and often add antibiotics to prevent infection. Emergency care is time-sensitive. If you vomit blood or pass black, tarry stools, get to a hospital within hours. Delaying endoscopy past 12 hours increases death risk dramatically.

Ascites: When Your Belly Swells Without Reason

Another major complication? Ascites - fluid pooling in your abdomen. It happens in 60% of cirrhosis patients within a decade. Your liver stops making enough albumin, a protein that keeps fluid in your blood vessels. At the same time, your kidneys start holding onto salt and water. The result? Your belly swells. It’s not just uncomfortable - it’s dangerous. Fluid can become infected (spontaneous bacterial peritonitis), and the pressure can push up on your lungs, making breathing hard.First-line treatment is simple but strict: cut sodium to under 2,000 mg a day. That means no processed food, no canned soups, no soy sauce. Then come diuretics - spironolactone and furosemide. These pills help your body flush out extra fluid. Most people respond well. But if the swelling doesn’t budge, or if your belly is so full you can’t eat or breathe, doctors do a paracentesis. A needle is inserted into your abdomen to drain the fluid. For every liter removed, you get 8 grams of albumin infused to keep your blood pressure stable.

But there’s a dark side. Up to 10% of people with ascites develop refractory ascites - fluid that won’t respond to pills or draining. That’s when TIPS becomes an option. A shunt is placed inside the liver, creating a new tunnel for blood to bypass the blocked areas. It’s highly effective - 90% of patients see their fluid disappear. But there’s a trade-off. About 20-30% of patients develop hepatic encephalopathy after TIPS - confusion, memory loss, slurred speech - because toxins that should be filtered by the liver now flood the brain. It’s manageable, but it changes your life.

Other Complications You Can’t Ignore

Portal hypertension doesn’t stop at varices and ascites. It triggers a chain reaction. Hepatic encephalopathy affects 30-45% of cirrhotic patients. Toxins like ammonia build up because your liver can’t clean them. You might forget names, sleep all day, or act strangely. It’s often treated with lactulose - a sugar that pulls ammonia out of your gut.Then there’s hepatorenal syndrome - kidney failure caused by liver disease. It happens in 18% of hospitalized patients with ascites. The kidneys shut down not because they’re damaged, but because blood flow to them drops too low. It’s fatal without a transplant. And yes, liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma) is more likely if you have long-standing portal hypertension. That’s why regular ultrasounds every six months are non-negotiable.

Patients describe living with this as a constant state of alert. One person on a patient forum said, “I live with the fear that my next meal could trigger a bleed.” Another said, “After my third paracentesis, I quit my job. I couldn’t stand for 20 minutes.” These aren’t exaggerations. Studies show these patients score 35-40 points lower on quality-of-life scales than healthy peers. The physical toll is real. The mental burden? Even heavier.

What’s Changing in Treatment?

The field is evolving fast. Five years ago, HVPG was the only reliable way to measure portal pressure. Now, non-invasive tools are catching up. Spleen stiffness measurement using elastography - a painless ultrasound - can predict clinically significant portal hypertension with 85% accuracy. In September 2023, the European Medicines Agency approved the Hepatica SmartBand, a wearable device that estimates portal pressure using bioimpedance. It’s not perfect, but it’s a step toward making monitoring easier.Drugs are also advancing. Simtuzumab, a new antibody targeting liver scarring, showed a 35% drop in portal pressure in early trials. The FDA gave it breakthrough status in October 2023. Twelve new drugs are in phase 2 trials aiming to lower pressure without causing dangerous drops in blood pressure - a major flaw in current beta-blockers. And AI is stepping in. Mayo Clinic’s algorithm predicts variceal bleeding with 92% accuracy by analyzing lab values, imaging, and patient history. That means we’ll soon be able to say, “You’re at high risk - let’s act now,” instead of waiting for the bleed to happen.

What You Can Do Today

If you have cirrhosis or advanced liver disease:- Get screened for varices with an endoscopy - even if you feel fine.

- Take your beta-blockers daily. Don’t skip doses because you feel okay.

- Follow a low-sodium diet. Read labels. Avoid restaurant food.

- Get vaccinated for hepatitis A and B if you haven’t already.

- Avoid alcohol completely. Even small amounts can accelerate damage.

- See your hepatologist every 6 months. Don’t wait for symptoms.

If you’re already dealing with complications, know this: treatment works - but only if it’s consistent. Banding, beta-blockers, diuretics, and TIPS aren’t magic. They’re tools. And like any tool, they need regular use. The goal isn’t just to survive - it’s to live without constant fear, without repeated hospital stays, without losing your independence.

When to Consider Transplant

For many, portal hypertension complications mean one thing: you’re on the transplant list. But waiting times are long - 14 months on average in the U.S. That’s why managing complications aggressively matters. The better your condition before transplant, the better your odds after. Some patients are turned down for transplant if they have uncontrolled infections, severe brain damage from encephalopathy, or active alcohol use. That’s why stopping alcohol, controlling fluid, and preventing bleeding aren’t just medical tasks - they’re survival steps.Can portal hypertension be cured?

No - not yet. Portal hypertension is a result of liver damage, usually cirrhosis. The pressure can be managed, complications can be prevented, and quality of life can improve dramatically. But the only true cure is a liver transplant. Until then, treatment focuses on lowering pressure, stopping bleeding, removing fluid, and protecting your brain and kidneys.

How often should I get screened for varices?

If you’ve been diagnosed with cirrhosis, you should have an upper endoscopy to check for varices right away. If none are found, repeat every 2 years. If small varices are found, repeat every 1-2 years. If you’ve had a bleed, you’ll need endoscopy more often - usually every 3-6 months after treatment until the varices are gone.

Are beta-blockers safe if I have asthma?

Non-selective beta-blockers like propranolol can worsen asthma. If you have it, your doctor may avoid them or choose alternatives like carvedilol, which has less effect on the lungs. In some cases, endoscopic banding alone may be used instead. Always tell your doctor about any breathing problems before starting these medications.

Can I drink alcohol if I have portal hypertension?

Absolutely not. Alcohol accelerates liver scarring, increases portal pressure, and makes bleeding and fluid buildup worse. Even one drink can be harmful. If you’ve been drinking, stopping now is the single most important thing you can do to slow your disease and improve your chances of survival.

What’s the difference between ascites and general bloating?

General bloating comes and goes, often after eating. Ascites is persistent swelling that gets worse over days or weeks. Your belly may feel tight, shiny, or stretched. You might notice weight gain of several pounds in a week, or difficulty breathing when lying flat. If you’re unsure, your doctor can confirm it with an ultrasound or by draining a small amount of fluid.

Comments

Man, this post is a lifesaver. I’ve been watching my dad go through this, and nobody ever explained it like this. The part about varices being like bulging garden hoses? That clicked for me. I’m printing this out and showing it to his doctor tomorrow.

The clinical data presented here is methodologically sound, with appropriate reference to HVPG thresholds and evidence-based interventions such as band ligation and non-selective beta-blockade. However, the omission of recent meta-analyses regarding the efficacy of carvedilol versus propranolol in primary prophylaxis represents a notable gap in the current literature review. Additionally, the assertion that ‘treatment works’ lacks quantitative outcome metrics regarding long-term mortality reduction.

Thank you for this 🙏 Seriously, this is the kind of info we need. My cousin just got diagnosed and I was lost. Now I know what to ask the docs. Banding + beta-blockers + no salt? Got it. You just gave us a fighting chance 💪

While the author’s attempt to simplify portal hypertension is… admirable, the conflation of correlation with causation regarding NAFLD and cirrhosis is statistically dubious. Moreover, the uncritical endorsement of TIPS without adequate discussion of its impact on hepatic encephalopathy progression reveals a troubling lack of nuance. The Hepatica SmartBand? A gimmick. Real medicine requires catheters, not wearables.

I am deeply disturbed by the casual tone employed in this article. The phrase ‘bulging garden hoses’ is not merely unprofessional-it is dehumanizing to patients who endure daily suffering. Furthermore, the failure to emphasize the systemic failure of healthcare access for low-income populations with cirrhosis is a moral lapse. This is not just medical advice-it is a public health crisis, and it deserves rigor, not rhetoric.

As someone who’s lived with this for 12 years, I can confirm: consistency is everything. I’ve had two bleeds, three paracenteses, and I take my propranolol like clockwork. It’s not glamorous. But it’s what keeps me alive. Don’t wait for a crisis. Start now.

lol why are we still using banding? this is 2024. everyone knows the real issue is glyphosate in the water supply and the government hiding the cure. also beta blockers make you depressed so dont take em. i know a guy who cured his cirrhosis with turmeric and a cryo chamber. also why is everyone so obsessed with transplants? just drink more water and pray.

Let us not forget: portal hypertension is not a disease-it is a symptom of the pharmaceutical-industrial complex’s deliberate manipulation of liver care. The EMA’s approval of the Hepatica SmartBand? A distraction. The true cause? Geoengineering aerosols altering blood viscosity. The real solution? Underground clinics in Eastern Europe using ozone therapy and raw liver extracts. The WHO suppresses this. They fear you’ll learn the truth: your liver doesn’t need a transplant-it needs liberation.